Was ZELDA: BREATH OF THE WILD Inspired by Disney's Magic Kingdom?

Discovering the Imagineering Design Principles that Guided Nintendo's Modern Open-World Classic

Note from the author (it’s me, Houston):

This piece was originally written and researched back in the simpler, more civilized era of May 2019. Soon after writing it, I turned it into a video essay over on my YouTube channel - which you can watch here. The video condensed lots of the content of this piece into smaller, easier-to-swallow sections - and yet it was still almost 30 minutes!

Anyway, given the bitter absence of theme parks in the world recently, I’ve been working on several themed-attraction-related pieces, and while I was in the midst of finishing some of them…I figured I’d go ahead and publish this one for anybody interested to read. Hope you enjoy!

Introduction

A fiery mountain looming in the distance, smoke swirling overhead. The remains of a once-great castle, now inhabited by monsters. Mystical forests with thick fog hiding something around every corner. Soft piano notes drifting slowly through half-forgotten melodies before trailing off and leaving only the sounds of blowing grass and distant streams. Tranquil vistas and peaceful countrysides accompanied by the ever-present feeling of adventure and the notion of nearby danger. This is Shigeru Miyamoto and Hidemaro Fujibayashi’s The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

A fantasy castle centered between multiple gates leading to faraway lands. A haunted colonial manor-house lurking in the hills like a crouching gargoyle. A futuristic city with a transportation system that never stops moving. A stretching main street that transports its guests back to a golden age of America that might never have existed at all. And above it all, a sense of adventure and wondrous discovery that just doesn’t belong in the real world. This is Walt Disney’s Magic Kingdom.

On the surface, it might not look like a video-game centered on a crumbling fantasy kingdom and a theme park centered on rides and attractions have that much in common. But when playing Breath of the Wild and when visiting Walt Disney World, I always feel the same emotions. Maybe it’s because they both give me a glimpse of what heaven is like. Or maybe it’s because the creators of both Breath of the Wild and Disney Parks use similar techniques to immerse their players and guests in a fantasy world that allows them to escape their own.

In this piece, which I wrote several months ago, I attempt to explore the crossover between theme park design and video-game design, and to ask the question: could Breath of the Wild and Walt Disney World’s successful visions (and business empires) stem from similar design principles? This question requires some background on both properties, the how-and-why of their creation, and eventually the crossover between their shared models of immersive environmental storytelling. Let’s get into it.

Background on Zelda: Breath of the Wild

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is widely considered to be one of the greatest “open-world” video-games ever created. When it was released in March of 2017, the game was quickly hailed by critics as one of the best Nintendo releases in years.

Wired UK said, “Breath of the Wild is a masterpiece.”

IGN called it, “a masterclass in open-world design and a watershed game that reinvents a 30-year-old franchise.”

TIME said, “it feels like a mind-blowing mic drop to the sort of ‘open world’ games…the industry seems bent on proliferating.”

And within a year of its release, Breath of the Wild (BOTW) had become the best-selling Zelda game of all time. But what exactly makes BOTW different from all the rest of the Zelda games? Let’s step back.

The Legend of Zelda was released in America for the NES in 1988, spearheaded by its Japanese creator, Shigeru Miyamoto. Even in the rudimentary 8-bit game, with characters made out of pixels and simplistic left-right-up-down controls, adventure and discovery were a huge part of the success. Miyamoto often cited his childhood growing up in the country and his experiences of exploring the nearby forests, mountains, and caves as the personal inspiration for a game where the primary goal was exploration. The original Legend of Zelda, after all, is widely-considered to be one of the first pioneers of open-world gameplay.

What’s an open-world game? I mean, you probably know this already, but it’s a type of experience where the players are presented with a sprawling map to explore and traverse at their own pace, often paired with a main storyline that can be completed using a variety of orders or approaches. Rather than having ‘levels’ to complete one after the other, an open-world game will often have various ‘missions’ or tasks to complete in any order across the map to eventually reach the ending.

In 1988, The Legend of Zelda’s map was one of the largest ever created, with countless secrets and hidden treasures for players to discover by using bombs to uncover caves, a raft to sail across the water and find islands, and fire to burn down trees and find secret passages below. The game was a smash hit, not only because it was fun to play solo, but because the hidden secrets and “choose-your-own-adventure” approach to the story quickly created a tight-knit community of *cough* gamers who all wanted to share the best secrets and strategies with one another.

Over the next 3 decades, the Zelda franchise expanded to more and more games every few years, from A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time to Link’s Awakening and The Wind Waker. Every Zelda game contained similar elements: an every man protagonist named Link trying to save the princess Zelda, a kingdom called Hyrule in turmoil after being overtaken by the evil Ganon, and various interpretations and takes on enemies, allies, and locations that all had new life breathed into them with every installment. The Zelda series has never been an ongoing story with each game as the ‘next chapter’ in a grand saga - instead, the title reinvents itself with every installment, taking elements that worked in previous entries and adding them to a reimagined world and gameplay. In a way, it’s an anthology series - and BOTW might be the most potent example of that concept.

Breath of the Wild envisions the kingdom of Hyrule 100 years after a great war where the evil “Calamity Ganon” overtook the land, desolating everything in his wake and occupying the countryside with his sinister forces. Many of the most iconic elements of the Zelda series are present in BOTW as ruins, forgotten legends, or crumbling remnants of what might have once been, in a way reminiscent of the Pevensie children’s return to a post-war Narnia in CS Lewis’s book Prince Caspian. The game takes the franchise back to its roots in multiple ways through story and iconography, but the chief example is the return to an open world approach with a story that can be completed in almost any order and an emphasis on exploration and the joy of discovery.

Exploration was the key driver behind The Legend of Zelda’s success, and 30 years later, it’s the driver behind Breath of the Wild’s success, too.

Of course, the difference between three decades of advancement in game technology is striking.

Breath of the Wild’s world ain’t made out of pixels anymore. The vistas, scenery and wildlife are near-photo-realistic - and often jaw-droppingly beautiful - while still maintaining the Anime-inspired cartoonishness of previous installments. BOTW’s physics engine and game mechanics have also been widely-praised for their creativeness and versatility; if the player sees a cliff, tree or wall, they can climb it. If the player has an axe, they can cut almost anything down - even the grass. If the player wants to climbs on the back of a bear or a deer and ride it, they can do that. And if the player wants to attach balloons to a raft and float it up to the sky like a hovercraft, they can do that, too. It’s often been said that if something in Breath of the Wild seems like it would logically work, it probably will.

The game also contains established rules and internal logic, like how holding metal weapons during a thunderstorm will inevitably result in being struck by lightning. A skilled player learns to use that internal logic to their advantage, such as by tossing one of their metal swords to an enemy during a storm and watching them face the consequences. And that internal logic applies to the game’s traversal as well; the joy of exploration in the game often comes from the fact that if the player sees a place in the distance they’d like to go to, it might take a while, but they can undoubtedly get there. Elevated vantage points often provide an eye-opening look at the sprawling world in the distance with no limits on where the player can explore - simply jump off with a glider and start flying toward the place they want to go next. Breath of the Wild is an extremely immersive game, chiefly because of the freedom and flexibility it provides players in their quest to explore Hyrule and stop Ganon.

The feeling of being able to go anywhere you want to go in BOTW is complimented by the fact that wherever you choose always feels real. The photorealistic sunlight and textures of the landscape, the different sounds of Link’s footsteps as he runs through grass or mud or water, the changes in weather conditions and various items to pick up along the way: it all serves to make you feel like you’re really there, and you can do any of the things you’d be able to do if you were. Nothing is off-limits or out-of-bounds. Not on the map, or in the possibilities of gameplay.

Background on Walt Disney World and Disneyland

Walt Disney’s Magic Kingdom opened in Orlando, FL in 1971, 16 years after the original Disneyland opened in California. Walt Disney World is quickly approaching its 50th anniversary in 2021; but before that comes, there are a myriad of changes and additions being made to the parks over the next few years - the recently-opened Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge expansion chief among them. Galaxy’s Edge actually might be one of the first Disney parks to take major inspiration from video-games. Most notably, the much-anticipated Millennium Falcon: Smuggler’s Run ride takes guests inside the cockpit of the famous spaceship and allow them to pilot it themselves. Orlando Sentinel journalist Gabrielle Russon described it as "essentially a giant video game moving in real time.” Beyond that, though, the Imagineers behind Galaxy’s Edge have often stressed the commitment to immersion driving it. When guests enter the gates of the new themed-land, they are meant to feel as though they have traveled to a completely different planet called Batuu. As such, none of the merchandise sold in Galaxy’s Edge features the Star Wars logo, because it’s meant to represent merchandise that would actually exist within the Star Wars narrative. The food is also intricately-themed to alien dishes, the cast-members (Disney’s label for employees) are all in-character residents of Batuu, and even drinks like Coca-Cola have alternate logos in the alien language of Arubesh.

What does this have to do with video-games? Well, in the past, the only way for Star Wars fans to feel immersed in the world of their favorite movie series was to play games like Star Wars: Battlefront II, Star Wars: The Force Unleashed, or even the LEGO Star Wars titles. Games like these were beloved for giving players that extra level of connection to the Star Wars universe, allowing them to interact, battle, and play within it instead of just passively watching a movie screen. With Galaxy’s Edge, that dream embodied mainly through video-games up till now comes to life in a real and tangible way. Guests at Galaxy’s Edge don’t use a game controller to ignite their lightsaber - they actually ignite their lightsaber.

Disney’s commitment to immersion, theming, and experiential entertainment goes back far before Star Wars was even around - in fact, before even video-games were around.

When Disneyland first opened in 1955, it already contained themed areas like Frontierland, Tomorrowland and Fantasyland, meant to teleport their guests to another time and place altogether through environmental and spatial storytelling. These were places like the much-romanticized Wild West, the buzzing metropolis of a futuristic city, or the fantastical kingdoms of Disney’s most iconic fairy tale adaptions. The famous plaque on the entrance to Disneyland, after all, reads “here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow and fantasy.” Since 1955, Disney’s transportive worlds have only continued to expand in scale; from The World Showcase at EPCOT, which allows guests to experience pavilions that transport them to eleven different countries around the globe, to Pandora: The World of Avatar in Disney’s Animal Kingdom, which constructs an alien realm of floating mountains and bioluminescent plants to immerse travelers in the (second) highest-grossing film of all time.

*editor coughs in Avengers: Endgame’s general direction*

Joe Rohde, the chief Imagineer on Pandora and legendary creative behind Expedition Everest, talked about this continually evolving focus on ‘immersion’ in 2017, connecting the experience to videogames:

“I do believe we’ve entered an era – and I think it may be because of gaming – where the expectation is no longer the expectation of a proscenium, but rather the expectation of a dome; the expectation that the story does surround me. If I turn my head, I’m still in the story. And that, I think, is where we are now arriving, in a world of world creation where you can enter and you’re free to look wherever you please and we will sustain you and keep you inside of a story, because it surrounds you.”

Rohde’s comments are revealing; Disney has always been focused on transporting guests to another time, another place, or another world, but their zero-in on sheer 360-degree immersion where the guest completely forgets they are in a theme-park at all? That element has mostly been a recent development. Rohde notes, of course, that this may have stemmed from gaming - although the immersive Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Disney’s main competitor, Universal Studios Orlando, might have had something to do with it too. Either way, people certainly seem to enjoy coming to Disney parks to ‘experience the magic’ and willfully let themselves believe they have entered a world that is not their own…and they come by the hundreds of millions. Disneyland’s 1-millionth visitor entered its gates after only two months of being open, in September of 1955. Fast-forward several decades, and in 2017 alone, Disney parks worldwide had a combined attendance of 150 million visitors, with Orlando’s Magic Kingdom accounting for 20.45 million of those people. It remains #1 park in attendance, both in the US and worldwide. People love Disney’s magical, immersive, fantasy empire.

From here on out, this piece will often focus specifically on comparing Breath of the Wild and The Magic Kingdom in Orlando. Why choose this park instead of one of Disney’s more recent additions, or the Walt Disney World resort in Orlando as a whole? Because The Magic Kingdom is the expanded vision of Walt Disney’s initial dream of Disneyland in Anaheim; Orlando’s incarnation is almost the same as the original Disneyland, but as Disney put it in one of his last-recorded appearances in 1966: “Here in Florida, we have something special that we never enjoyed at Disneyland: the blessing of size. There’s enough land here to hold all the ideas and plans we can possibly imagine.” The Magic Kingdom is everything people love about Disney as a whole, distilled into one perfected open-space vision, and consequently, it’s also the most-visited theme park in the world. It makes sense to hold it up against the most successful Zelda title of all time.

Comparing Theme Park Design and Video-Game Design w/Mel McGowan

Former Imagineer Don Carson once stressed that his favorite video-games and his favorite theme-parks have three things in common: they let him be someone he could never be, they let him go somewhere he could never go, and they let him do something he could never do. Carson summarizes the Zelda/Disney parallel well: Breath of the Wild lets players be a fantasy warrior; Magic Kingdom lets guests be a pirate, a princess, a cowboy, or a citizen of a futuristic city. Breath of the Wild lets players journey across a vast, Lord of the Rings-esque landscape; Magic Kingdom lets guests go anywhere from a Tahitian Tiki Room to the land of Southern folktales and animated rabbits. Breath of the Wild lets players fight monsters and save princesses; Magic Kingdom lets guests visit ghosts in the great beyond and shoot lasers at aliens in the world of Buzz Lightyear. To a certain extent, video-games like Breath of the Wild and theme parks like The Magic Kingdom are designed to accomplish similar goals in completely different ways.

For the research in this piece over a year ago, I had the privilege to interview Former Imagineer Mel McGowan about the theme-park design process, its crossover with video-games, and how designers tell a story through an experiential environment. With Disney paying his way through grad-school, over 20 years ago McGowan got a Masters degree in “Environmental and Master-Planning” from California Polytechnical. Today, he continues to use his skillset as the co-founder and Chief Creative Officer of PlainJoe Studios in California, where he “creatively leads the unique multidisciplinary SPATIAL STORYTELLING℠ studio, which integrates the multiple disciplines of master planning, architecture, interior design, show set design, environmental graphics, and themed attraction design in the creation of compelling experiences and environments around the world.”

Asked to summarize what he did for Disney during his 10-year stint working for them in California, McGowan says:

“Specifically at Disney, a lot of my focus was on integrating the existing properties that Disneyland has and new Disneyland hotels that they had acquired…it was really urban development to un-pave the parking lot and put up paradise. A lot my focus [was on] creating a resort destination and weaving in Downtown Disney as that kind-of bridge between the public realm of Harbor Boulevard and transportation gateway into the heart of the Disney properties, to weave together all the different hotels, and then to do the master-plans for the Disney hotel property - turn that into a Disney resort.”

McGowan has never worked in the video-game industry, but he unmistakably acknowledges the crossover between the two art-forms. He says:

“Yeah, that’s something I’ve been pushing - the whole integration of [the two], and I think it’s already happened in some of the emerging entertainment design programs, where there’s a clear understanding that even at the simplest level, they [are both] just simply production design. It’s definitely literally the same skillset, whether you’re designing something that will only ever appear digitally, whether conceptual drawings for a themed land, or whether it’s production design for a film.”

McGowan continues, mentioning the industry’s newfound practice of training the next generation to work in either field, depending on which is the most relevant:

“You’re definitely seeing that now with schools like Carnegie Mellon and CalArts, where…they’re training the kids up, almost intentionally, to be able to go wherever the market goes. You know, my focus is obviously more of the general production design and spatial storytelling. I’m not deep into video-games, gamification, strategy kind-of stuff. But certainly from that skillset of production design, I think there are definitely plenty of parallels there.”

Breath of the Wild and The Magic Kingdom both tend to generate a sense of awe and wonder in their players at the world around them and the grandeur of that world. When asked about what creates this sense of immersive wonderment, McGowan says:

“I think one of the biggest things to me is…I did an article on Themed Attractions [Website] just on backstory. [Backstory is] something that a lot of visual artists and guys that draw really well don’t necessarily appreciate. Just like they don’t appreciate the bean counters, the accountants, and the finance guys (laughs)…I think unfortunately in some cases, not always, they have an under-appreciation for writers. The idea of backstory is fundamentally [an exercise of] creative writing. To me it’s not about flowery writing or naming or any of that, it’s really more the idea of, before you just start drawing and visualizing, really taking the time to work through internal logic and backstory.”

McGowan continues:

“One of the reasons [backstory is important], and [Pandora: The World of Avatar] is a great example, is that anybody can step into that environment and be immersed, but part of the subtle psychology of it is that it’s not just some guy saying ‘hey, I’ve got floating islands and waterfalls in the sky!’ You know, there’s a backstory and there’s an internal logic to it. Even though it’s beautiful either way, the thing that makes it believable is that idea of this historical origin story that pulls it all together.”

Mr. McGowan is a Christian, and his company, PlainJoe Studios, often also works to improve church architecture and urban-planning to create more communal religious spaces and environments of worship. He mentions several times that he believes the reason people respond so well to an attraction with a backstory stems from the fundamental desire in humans around the globe for a Genesis-like creation narrative in history. He also notes that Disney has been retroactively adding backstory to some of their resorts to improve the legibility and internal logic of the spatial storytelling:

“…That’s why I think Disney has been able to be really successful, even with the first Disney motels that they were doing with Caribbean Beach and Port Orleans. Even though those are really just simple Holiday Inn motel structures…someone actually sat down when they were first developed and wrote out a backstory and history and named the Sassagoula River. It’s the same process they used when they went back and retrofitted Disney Springs and stuff - it’s the simple idea that it now represents a Florida town. Not that big a deal, but it’s just the idea that it’s not just another sexy retail center, it’s actually trying to tie into this narrative of a Florida town developed around a spring. It really gives you an internal logic around everything.”

Many players of Breath of the Wild cite the game’s sense of exploration and discovery as one of the key reasons they enjoyed playing it. Could Disney parks share that sense? McGowan had this to say:

“Well it’s funny because there’s this tension - and this isn’t just in Imagineering, this is in urban planning and urban design - there’s a tension with the idea of legibility, meaning something that’s easy to orient yourself and find your way around. There’s this writer named Kevin Lynch, and a lot of his focus was on the ability of people to feel a sense of comfort and reassurance and even joy in feeling like they have a good grasp of their world and their environment and their city, and the elements that have that sense of comfort and legibility. He identified things like districts, paths, edges, landmarks. [These are] things like Cinderella’s Castle, things like Main Street USA - he was really great at articulating those elements that really were pretty intuitive to Walt Disney. So for example, one of his elements was the idea of districts - we automatically want to break the city into some different bite-sized chunks, and of course, lands are the best example of that. [The Magic Kingdom] is not just this 100-acre amusement zone, you have these nice bite-sized chunks; 5 to 12-acre lands that you can know when you’re entering these different diegetic realities.”

McGowan continues, countering the importance of ‘legibility’ with the aforementioned sense of ‘discovery’:

“So that’s on the legibility side of the argument. The other end of that spectrum is the idea of this sense of discovery - I think Ray Bradbury called it being ‘deliriously lost.’ So you know, you drop me in the middle of Rome, man, and just the ability to roam for hours and be completely stoked that I have no idea what’s going to be around the next corner? There are certain places in the world that you almost don’t want to find your way back to your hotel room because there’s just so much goodness around every corner - it’s like, how deep could this rabbit hole go? It’s like Alice in Wonderland, you just go deeper into the hole and get ‘curiouser and curiouser.’ So that idea, to me, is almost like a careful, delicate dance. As a master-planner, this would go in terms of laying out paths in a video-game - because you’re still doing master-planning and site-planning on game maps - there’s that careful balance. A lot of people think Walt Disney just brought this Parisian type hub-and-spoke model to the table, but what he really brought was this sort-of ‘perfect balance’ orchestration.”

McGowan elaborates on Disney’s “perfect balance”, noting the importance of areas that provide order, while also allowing guests to get lost at their leisure:

“Walt Disney liked the idea of having that central hub and the idea of being able to return to this neutral zone; this peaceful plaza in the middle to know where you’ve been and where you want to go. It’s kind-of like how CS Lewis talks about the ‘wood between worlds.’ And there’s power to that, so that you wouldn’t feel lost and disoriented, or frustrated and mad. But again, the cool thing is that you could be in a canoe behind the Rivers of America and completely feel not only miles away from the Interstate 5 freeway, but also miles away from that central formal plaza hub. And same thing in Jungle Cruise, you’re just 100 yards away, but you feel completely lost in the back-alleys and jungles of that world.”

Disney and Breath of the Wild share another thing in common: they envelop their guests and players in a story that feels simultaneously bigger than them while also completely in their control. Mr. McGowan elaborated on what makes a person feel as though they’re a part of a ‘story’ in this way:

“I think the simple answer is your definition of story. The idea that story is ‘act 1, act 2, act 3’ and you have to follow this protagonist and use a chronological sequence of events…that’s not necessarily the definition of ‘story’ that I would use and that Disney uses, especially when you talk about Imagineering and spatial storytelling. To me, for example, I think it was inherent in the Disneyland and Magic Kingdom models that even though there were these multiple genres and multiple lands, there’s no doubt about it that Disneyland represents a cohesive philosophical whole. There is a sense of overall identity to the composition. To me, there is this unique reflection of both the person of Walt Disney and also of mid-century America as it turned ahead in the 20th century. So, you know, you’re literally stepping into Walt’s childhood - and his childhood is also the surrogate for Americans of the 20th century…So not to get too abstract, but all I’m saying is that even though it has different lands and different genres and different settings, they were all setting up a cohesive story. The story of America’s well-being, the story of aspiration and nostalgia, of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy. That does have a soul. And it’s radically different from something like, say, [Universal’s] Islands of Adventure, where if you asked me ‘from a spiritual, big-idea, core emotional level, what does Cartoon Lagoon have to do with Jurassic Park? What does that have to do with Harry Potter?’ And the answer is not much, really - those are just what the lawyers were able to cobble together. There’s not really a soul to that park, and it’s really just kind-of a hodge-podge.”

Mr. McGowan concludes by noting how the entirety of Walt Disney World, not just The Magic Kingdom, plays into this concept:

“And then again, the way the Magic Kingdom model works, I’d say that Disney World as a whole works really well. Because if you think about it, even though each park has their own lands and what have you, even just the four big parks really complement each other nicely…and they all create this cohesive vision of the world as it should be, and ya know, people get it.”

With Disney’s empire reigning over the theme-park industry, people seem to “get it” indeed. But how do Mr. McGowan’s Imagineering insights apply to Breath of the Wild? Let’s pull it all together.

Breath of The Wild and The Magic Kingdom

Disney’s Magic Kingdom does not have the same stylistic or creative DNA as every videogame. In fact, it might not even have a similar DNA to many video-games at all. The Magic Kingdom and Breath of the Wild, however, undoubtedly contain similar ideas and methods of conveying those ideas to the respective player or guest through their immersive, interactive worlds and carefully constructed environmental storytelling.

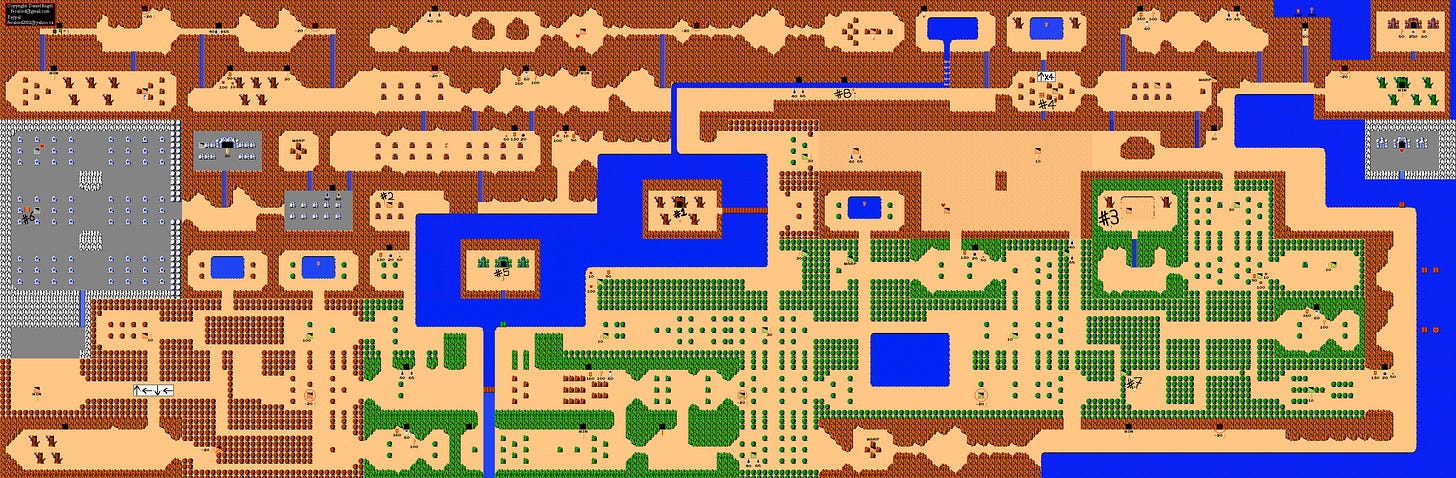

Undoubtedly, there are plenty of surface-level similarities between the two that cannot be overlooked. Some, like online blogger Samuel Cook, have even speculated that Breath of the Wild’s open-world map was very specifically and intentionally designed to mirror that of The Magic Kingdom in an almost post-apocalyptic vision of what it could look like after centuries of war. It’s hard to deny some striking similarities: both maps feature a large fantasy castle directly in the center; both maps have a sword in the stone just north of that castle; just west of the castle on both maps, there is a region with “Frontier” in its name; and just south-west of the castle, both have an Orient-themed marketplace which features magic carpets. There are other little touches scattered throughout - small locational placements and potential references that could be intentional or could be pure coincidence. Some believe that the Japan-based game designers might have based the map on the also-similar layout of Tokyo Disneyland.

But whether or not Breath of the Wild was deliberately designed to directly mirror the surface-level elements of Magic Kingdom’s geographical layout and design, the principles that make the game work are almost the exact same ones that make The Magic Kingdom work.

Mr. McGowan had much insight to offer about the Imagineering process and its relationship to video-games, though he had never specifically played Breath of the Wild. He acknowledged up-front that the skillset behind creating a game-world and the skillset behind Cook’s comparison of the area around the castles on both maps creating a theme park are the same, and it’s true: both blatantly involve production design and urban planning. The ways Magic Kingdom and Breath of the Wild’s maps mirror each other go beyond simplistic visual parallels. To start with, both maps are divided into regions, or as McGowan put it, “districts”, to maximize legibility and create a diverse array of locations to traverse. At The Magic Kingdom, these regions are the “lands” like Tomorrowland and Adventureland, all fanning out like petals on a flower from the central hub of Cinderella’s Castle.

In Breath of the Wild, the map is also split into districts or regions, with each one varying in biome, natural features, and weather conditions, and inhabited by different tribes of enemies and allies to encounter along the way. This idea of having individual regions or “lands” with their own internal consistency, as McGowan mentioned, probably goes back to satisfying urban city planning at its core. It is also affirmed, however, by some of the most widely-recorded and publicly-acknowledged techniques of Imagineering: “Mickey’s 10 Commandments.” These 10 ‘rules’ of attraction design were put to paper by Imagineer Marty Sklar in 1987 when he was the chief creative behind EPCOT Center. Among them are points like '#1: Know Your Audience’ and ‘#3: Organize the Flow of People and Ideas.’ The commandments that most affirm the ‘region/district/land’ layouts of both Magic Kingdom and Breath of the Wild are ‘#4: Create a Visual Magnet’ and ‘#7: Tell One Story at a Time.’

‘#4: Create a visual magnet’ is most widely-applied to The Magic Kingdom as a whole because of the park’s prominent use of Cinderella Castle as an anchor point for guests, with the towering structure serving as a compass-like constant that they can see from almost anywhere in the park. Marty Sklar’s full ‘commandment’ says “#4: Create a ‘weenie’ - Lead visitors from one area to another by creating visual magnets and giving visitors rewards for making the journey.” This clearly encapsulates the purpose of Cinderella Castle well, but many people forget that the individual lands of Magic Kingdom also have their own ‘weenies’ (Walt Disney’s original term for a visual magnet) presiding over them, too.

Adventureland has The Enchanted Tiki Room towering over the area and visible from anywhere within its borders. Tomorrowland has the Astro Orbiter, a spinning spaceship ride flying high above the futuristic city below. Frontierland has Splash Mountain, the Song of the South-themed dark-ride visible anywhere from Liberty Square to Tom Sawyer Island and quickly attracting people in its direction.

Breath of the Wild similarly uses visual magnets or ‘weenies’ to guide players, both on the map as a whole and within each region of that map. As established, both Magic Kingdom and Breath of the Wild have a fantasy castle in the center, and much like Cinderella Castle, Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule Castle is visible from just about anywhere on the map, sinisterly looming in the distance as an ever-present reminder of the threat posed by Calamity Ganon that must be stopped. Like its theme park counterpart, however, Breath of the Wild also contains other visual magnets within its individual regions: Sheikah Towers.

In every one of the regions in Breath of the Wild - 15 of them in total - a massive tower must be scaled to reach the top and unlock a map of the area. Many open-world video-games use this concept of reaching checkpoints that contain portions of a map to fill in, but Breath of the Wild also uses its towers as visual magnets or ‘weenies’ to guide the player at all times. At almost any point, no matter their location on the map, players can look off into the distance and see one or multiple towers guiding their way to whichever region they’d like to head toward next. And when they finally reach a tower, they can climb it and get the benefit of seeing things from a bird’s eye view. The concept is surprisingly effective in constantly keeping the player looking off to the horizon for their next adventure, and undoubtedly plays into that feeling of exploration so many have praised the game for achieving.

Marty Sklar’s other relevant commandment here is probably “#7: Tell One Story at a Time”, which states “If you have a lot of information, divide it into distinct, logical, organized stories. People can absorb and retain information more clearly if the path to the next concept is clear and logical.”

The connection of this point to the ‘lands’ of The Magic Kingdom and the regions of Breath of the Wild is unmistakable: the split between each environment helps to organize the information and tell one story at a time. As Mr. McGowan mentioned a a while back, “[The Magic Kingdom] is not just this 100-acre amusement zone, you have these nice bite-sized chunks; 5 to 12-acre lands that you can know when you’re entering these different diegetic realities.” Breath of the Wild also has another reason to utilize this concept: each of the regions in the game has its own story-based ‘quest’ that can be completed within it. There is no order to which quest has to be completed first, but each one is self-contained within the region it belongs to, and manages to inform how the player approaches the others. The game tells one story at a time.

There are many other connections between Mr. McGowan’s Imagineering insights and Marty Sklar’s “Mickey’s 10 Commandments” with Breath of the Wild, though to elaborate on all of them would take another paper entirely. Two more of Sklar’s commandments are things like ‘#9: For Every Ounce of Treatment, Provide a Ton of Fun’ and ‘#5: Communicate with Visual Literacy.” Breath of the Wild successfully achieves #9 in a few ways, chief of which is its use of the opening “Great Plateau” section of the game and the following “Shrine Challenges” to essentially give the player tutorials on how to use their tools and controls while also providing a fun way for them to learn combat. The game also “communicates with visual literacy” from start to finish in a way unlike many other open-world adventures in its field; an abandoned temple, a dying maple tree, a horse stable illuminated by firelight in the middle of a thunderstorm - every sight in BOTW tells a clear story through imagery.

Breath of the Wild and Magic Kingdom are similarly interactive, too. Every tree in Breath of the Wild can be cut down, every animal can be hunted, every bush can be set ablaze and every lake can be fished-in. In The Magic Kingdom, there are very few facades or “fake” elements. Nearly every building can be entered. Every postbox in Main Street USA can really be used to send mail. Even the waiting queues for attractions have added ‘interactive’ elements, like a giant touchscreen in The Many Adventures of Winnie The Pooh that lets guests wipe their hand through a wall of honey, or the drawers in The Haunted Mansion queue that keep mysteriously opening again after a guest tries to close them. Like an open-world game, it’s an environment where everyone feels connected and in control of their own destiny.

Conclusion

Breath of the Wild and The Magic Kingdom are both concerned largely with using their locations and grander settings as characters in and of themselves, encouraging their respective players or guests to explore those settings as part of the adventure.

In Breath of the Wild, the kingdom of Hyrule is not just a backdrop to the story of The Legend of Zelda, but it actually embodies the story in a more tangible and microcosmic way than any Zelda title before it. The desolated, post-apocalyptic, moss-covered wilderness reflects the evil brought on by Ganon and reminds the player of the still-lingering threat as they traverse through the decaying wasteland. Yet among this destruction, there are still pockets of beauty and tranquility - places where the mother nature has started to reclaim what belongs to her, where wildlife continues to thrive and graze in the forests and fields, and where the scenic splendor proves that maybe humans do more harm than good to the world around them, in their constant battle for civilization. Breath of the Wild’s world always tells a story - a story of a land in need of a hero, a story of the villagers and regular people who have been displaced by war and had to start anew, and a story of the natural world’s conflict with human invention and technology. Exploring that world is all the more rich and fulfilling because of the story told by the physical environment, and the player’s command over what happens next.

The story of The Magic Kingdom, like that of Breath of the Wild, is one that changes for every guest, enveloping them in the action and making their experiences feel like a moving picture of its own unique caliber. Yet the environment that guests enter when they arrive at the park also has its own internal logic and consistency; the artful tale The Magic Kingdom tells is that of its creator: Walt Disney himself.

Walking through the lands of Magic Kingdom feels like walking through the heart, soul and mind of Walt Disney. And indeed, every one of the individual lands reflects an intrinsic part of Walt’s personality and passions that he wanted to convey through his own theme park. Liberty Square speaks to Walt’s enthusiasm for American history and desire to educate young people about the origins of their country. Main Street USA represents Walt’s nostalgic yearning for a simpler time in America, like that of his childhood growing up in a small town in Missouri. Tomorrowland epitomizes Walt’s love of progress and technology- the way he always embraced the future instead of fearing it. Fantasyland is maybe the clearest metaphor of all, perfectly embodying the fondness for imagination and fairy tales that inspired Disney’s films in the first place.

This paper started out asking the question: "could Breath of the Wild and Walt Disney World’s successful visions (and business empires) stem from similar creative principles?” My answer is unequivocally “yes.” The insights and design theories postulated by two Imagineers prove that there might be something inherent in effective design that will always be present wherever a great story is present. Whether the creators of Breath of the Wild were informed on Imagineering techniques is up for discussion, but either way, it’s clear that their genius and Walt Disney’s genius were both intuitive enough to know what really works from a player or a guest’s point of view. Maybe they both embody, as Mr. McGowan put it, design “that does have a soul.”

Thanks for reading this (obscenely long) piece! I’m planning to be writing more film and themed-attraction related content on this page in the near future, so feel free to subscribe with your email to get notified. Or don’t. Let’s be honest, I’ll probably post it on my Twitter, anyway.

Twitter at @blockbustedpod

YouTube at HoustonProductions1

Patreon at HoustonProductions1